Exhibition no. 10.- Painted faces. Group exhibition, painting, and drawing. From Friday, September 9th to Thursday, October 14th, 2016.

Any portrait that is painted emotionally is a portrait of the artist and not of the model

Oscar Wilde

Portrait has played an important role in the history of art, mainly in the definition of the political and social climate of each epoch. Contemporary portraiture, however, has become increasingly less representational and increasingly conceptual, addressing the complexities of personal identity through themes such as childhood, loss, gender, anonymity, tragedy, expression, etc. This exhibition of 28 works by 25 artists shows a very diverse group in the exploration of the theme and the struggle of similar problems of what it means to be an individual.

In Sonreir sin mirar a quien (Smiling without looking at who) by Norma Patricia Rodriguez and Nino tribu Surma (Surma tribe boy) by Elia Amador, the artists show us a warm indigenous beauty of two children that we can recognize as part of a rural environment in contrast with the work Nina burbujas (Little girl bubbles) by Alan Garcia, in which the artist introduces us to a who it seems most likely a city girl, playing with soap bubbles. But in all three cases, they refer us to that vulnerable position of all children: the fact of growing up and the loss of innocence that comes within.

This feeling for some people manifested as anxiety, is reflected in the work Oyeme como quien oye llover (Hear me as someone who hears the rain) by Alan G. Rodriguez (Frijolais), in which with its demanding hyper-realistic close-up style, it provokes a feeling of closeness with the anonymous teenager, striking in privacy.

In contrast, the loss of innocence for many other people is lived as a state of illusion. This can be seen in Ingrid Sosa’s Una mirada al espejo (A look at the mirror), in which with its characteristic color palette and complex textures shows an excited teenager experiencing her innate coquetry. In that same tuning, young people appear in seductive poses in the works Errores (Mistakes) by FbnVO, Nina (Girl) by Saul de Leon, and Lady Blue by Gorcha. Sin titulo I (Untitled I) by Araceli Rodríguez is marked by an idealized air, almost reverential, poignant and even cloying.

On the other hand, we encounter faces of women radiating another kind of energy, women which have left aside the innocence, and seduction finally appears. Simply as its own nature. in Bella Aya (Beautiful Aya) by Rowshkey; loose and free in Mujer fuerte (Strong woman) by Krogalac; natural and spontaneous in Vacaciones (Holidays) by Mel, and even in Aire (Air) by Barbara Barrera, in which the anonymous figure does not seem to be conscious of being photographed.

The bright colors and organic shape that float around the canvas of Quisiera ser ella (Wishing to be her) by Marcia Donato, emphasize the central image, with which the artist affirms herself in full consciousness, as distinct from the protagonist of her work. In this sense, the portrait gives the possibility of disguising itself, as in the work Sin titulo II (Untitled II) by Araceli Rodriguez, Carnaval (Carnival) by Gloria Rivera, Autoretrato (Self-portrait) by Xatrid, and C by Fabian. In all of them, to a greater or lesser extent, the characters are beset by the recognition of their true identity. And at the top of personification, as non-existent entities and a bloody dye are the works of La muerte de Ciclope (The death of Cyclope) by Nebleo and Khaleesi by Elia Amador.

Moving away from the literalness of the portrait, but following the line of bloodthirsty and anonymity, is the work La atemporalidad de una tragedia (The timelessness of a tragedy) by Jordy Israel Aleman Romero, in which we find a scene in which it seems a crime has been taken, that even when it has left traces, the only true witnesses of the transgression are two portraits. And perhaps the work Here is Johnny by Oscar Garduno, could be placed in this occasion as the witness or assassin.

In a similar mood, we find Frank Medellin’s Maniaco del humo (Maniac of smoke), in which the gesture of the portrayed person points out an anxious attitude that he calmed by smoking a cigar. That same quasi-schizophrenic quality is expressed in Mateo Pineda’s Meditacion continua (Continuous meditation), through which despite this apparent dementia, the protagonist declares that she would not like to be immobilized or discovered.

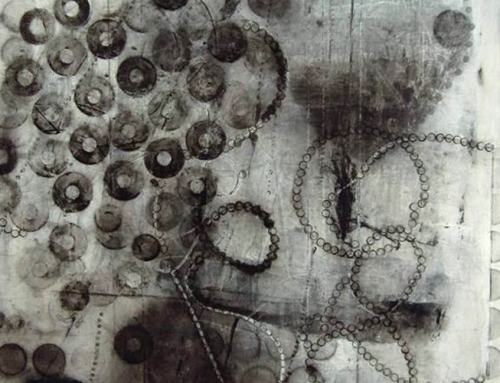

Finally, in a more abstract facet are the works Introspeccion I and Introspeccion II (Introspection I and Introspection II) of Jafet Gonzalez Gomez and Porque el deseo gira en espiral (Because the desire turns in spiral) by Veronica Rabell. In the first case, under a minimal aesthetic and a seriality that typifies, the artist shows us an inclination to ancient oriental art, while in the second, using digital techniques, the artist brings us back to the contemporary. Red head by David Cruz, then remains as the end of the reduction, leaving only a sketch of what makes up a face: a pair of eyes, a nose and a mouth.

We can conclude that for any rule that could be used to define a portrait, there will always be a work that defies that rule. At a certain moment, the portrait will seem to be more than a genre, but a blurred constellation of the guidelines suggested until now.